Fairfield County Sc Percentage That Cannot Read

Costly travel, hefty compensation, lack of accountability uncovered

EDITOR'South NOTE: This story was produced through a collaboration of The Post and Courier and The Voice of Fairfield Canton , an Uncovered partner.

WINNSBORO — J.R. Green seethed with anger as he read an article in his local paper. The school district he leads was on winter break, but Green couldn't cease fuming over the words on the page before him.

The Vocalization of Fairfield Canton reported that Light-green's district had failed to meet certain country academic benchmarks. The commodity cited statistics to prove it.

Bristling at the critique, the superintendent fired off an e-mail to his principals and school board. The missive, titled "False, Biased, and Misleading Reporting," blasted the paper and accused its reporter of "marginalizing our students, staff, and system."

"I want you to share this reporting with your staff then they understand the hostile media environment we face up," Green wrote that night in Dec 2018.

The fiery dispatch is emblematic of Dark-green's approach to uncomfortable questions and criticism during his nine years leading this high-poverty Midlands commune of roughly two,000 students.

In public forums, he has sidestepped questions almost his taxpayer-funded bacon and other points of contention. For years, he has rebuffed attempts to reveal how he spends thousands of dollars in public money.

It'south one striking instance of how easily regime officials in South Carolina tin shield information from the public. In its investigative serial Uncovered, The Post and Courier is partnering with local newspapers to help shine a light on questionable conduct, and hold the powerful to account in areas with few watchdogs.

Across South Carolina, especially in rural communities that have get news deserts, officials are less likely to be pressed on their decisions, and more than prone to set the public agenda themselves.

In this latest installment, a Post and Courier articulation investigation with The Vocalisation pierced the veil that shrouds Fairfield schools, one of Due south Carolina's smaller, just well-funded, school districts.

Largely thanks to taxation revenue from a local nuclear power plant, Fairfield schools collect more than money per student than any other district in the state.

Year after twelvemonth, top school district officials use a hefty chunk of the money for travel to pricey conferences at tourist resorts beyond South Carolina and the country, the newspapers found.

Between 2017 and 2020, Greenish's office and Fairfield'south seven board members charged taxpayers for trips just almost every calendar month during the schoolhouse calendar. That included dozens of trips to conferences at waterfront resorts in Charleston, Myrtle Beach and Hilton Caput.

The almanac pecker for those and other trips? Nigh $50,000 — enough coin to encompass the salary of an additional classroom instructor.

With a $192,000 salary and his own $42,000 discretionary account, Green besides charges the public for his commune travel.

At the same time, the board has extended Green fatty bonuses, contingent upon Green receiving passing grades in thin almanac evaluations that lack measurable goals.

The one-page forms are filled out anonymously by board members and leave little room for comments or discussion — less rigorous than some get-go grade report cards.

That's contributed to a vacuum of accountability in Fairfield, a community that does non have a daily paper.

The Voice publishes weekly, holding the district to account when student functioning dips, or when summit officials endeavor to obscure their public spending. Light-green views that reporting – on scores, his evaluation and spending and his failure to disembalm an out-of-country, overnight schoolhouse-sponsored trip to the lath – as an attack on the commune.

In response, Green has warned commune employees confronting speaking to The Phonation, directing them, for the last two years, to send whatsoever information for The Vox (pupil achievements, honors, etc.) to the schoolhouse'due south man resources department for approving to be forwarded to The Voice. That information never gets forwarded. Then, Green took the matter a step further: He started the district's own publication.

The Fairfield Postal service is distributed weekly around the county, ofttimes filled with campaign advertisements or columns penned by politicians.

"The Post is an opportunity to really lift up the good things that are happening," Light-green said.

Taxpayers underwrite the costs, to the tune of $27,000 a year.

Green, whom the Southward.C. Association of Schoolhouse Administrators named the 2021 Southward.C. Superintendent of the Yr, did concur to speak with The Mail service and Courier. He and then conducted a lengthy discussion of the newspaper's collaboration with The Voice at a May eleven school board coming together.

When reporters arrived, he asked them to exit, citing the district'due south social distancing rules in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Still, a livestream circulate Green's remarks to the lath — a defiant rant that stretched nigh 40 minutes. He fiercely defended the commune's spending of taxpayer coin. He roundly criticized the state's instruction statistics, which he described equally an incomplete picture of the district'due south progress with students.

Light-green also accused a reporter of questioning him because he is Black, describing this and other reporting by The Post and Courier as a suspicious try to target people of color.

In other conversations with a reporter, Green stressed 1 betoken in a higher place all: He despises and distrusts The Vox. When asked to cite examples of the newspaper's reporting, Green pointed to what he insists was a demeaning tweet sent past a Voice freelancer in 2019, months after he had cutting ties with the newspaper. Otherwise, he just spoke generally nearly coverage he described equally negative.

"I take confessed in (church) that there is animosity in my eye," he said near the newspaper and its publisher. "I have to pray that the Lord removes it."

'Change the culture'

Greenish didn't always quarrel with the local newspaper.

"Community Turns Out to Meet New Superintendent," read the headline in The Vocalisation, above a photo of Green smiling for a photographer when the district hired him in 2012.

Green carries three degrees, as well as a doctorate in didactics leadership from the Academy of South Carolina. Every bit a principal and assistant superintendent in Chesterfield Canton, he helped a high schoolhouse bring up its grades on its state written report card, and hit its year-over-year targets for improving pupil functioning.

Meanwhile, Fairfield schools were rocked by extreme turnover in the commune's elevation position. Before Green arrived, Fairfield cycled through 12 superintendents in 20 years amid a period of dysfunction among the board. Local residents chosen the district South Carolina's "graveyard for superintendents."

The surrounding community as well faced disruptions. Once-bustling Winnsboro, the county seat, hosted the headquarters of Uniroyal Tire Visitor. Simply the town lost businesses, jobs and somewhen its hospital afterward the construction of Interstate 77 bypassed the community in the 1970s. The surrounding countryside remains largely rural, dotted with rolling pastures and horse and cattle farms.

Fairfield's teachers and administrators brainwash a student body where school officials say almost xc percent of the children authorize for free or reduced lunch.

Green vowed to "modify the culture" in an expanse that needed help. He stressed teamwork and an open up relationship with the community. He has maintained a visible presence, regularly making appearances in front end of goggle box cameras for local news programs.

Only eventually, some of those promises were tested as Green'south decision-making came under tighter scrutiny.

First, lath members questioned why more than two dozen out-of-state and overnight trips were planned for student groups in 2015, including travel to New York Metropolis, Puerto Rico and the Bahamas. Board members questioned how much those trips would cost taxpayers. Green said he didn't know. The board authorized the trips anyhow.

Some board members also pressed Greenish on his use of the superintendent'due south fund, roughly $42,000 in taxpayer coin. Green has broad discretion to spend the money each twelvemonth as he chooses.

While deliberating the district's upkeep in 2017, then-board member Annie McDaniel asked why the lath couldn't become more details on his discretionary spending.

Light-green said he'd just share the information if the board voted to ask for it. Another board fellow member at the time, Paula Hartman, pressed farther.

"Does that mean that y'all won't give us that information?" Hartman asked.

"That means if the board directs me to provide it, I volition," Light-green said.

Beth Reid, and then the lath'due south chair, suggested Hartman submit an inquiry nether the S.C. Liberty of Information Act.

"If a person from the audition asked for that information, could they get information technology?" Hartman asked.

"Yes," Reid answered.

"So why tin't I?" Hartman asked.

A lack of access

The country's open records law is supposed to allow for the gratis flow of public information, then whatsoever media outlet or citizen can easily see how their government is operating and spending the public'due south money.

Simply the FOIA law is riddled with loopholes that officials can exploit to shield unsavory information from public view.

After a 2017 subpoena to the

constabulary, authorities agencies — for the beginning time — were allowed to charge residents and news outlets for costs that officials acquaintance with retrieving or redacting documents.

But with vague guidelines, the amounts calculated past the regime can far surpass what the average denizen can afford — hundreds, even thousands, of dollars.

At the same time, officials may freely ignore straight questions from citizens. Instead, they tin can insist that information simply be released if requested under FOIA. That way, they go along public information in the dark for weeks, or even months.

The flaws in the system present major roadblocks for cash-strapped local newspapers around the state, including The Voice of Fairfield County.

After lashing out at the newspaper's coverage of the commune's student performance in 2018, Light-green has not agreed to an interview with the newspaper in more than than 2 years, and has blocked other attempts past the newspaper to proceeds information for stories that highlight the schools.

The end result is dwindling accountability, and an environs that limits the local paper'south ability to carry out its First Amendment duties, said Lynn Teague, vice president of the South Carolina League of Women Voters.

"It sounds totally unacceptable," Teague said. "If I were a taxpayer in Fairfield, I would find information technology unacceptable."

Green said The Voice is at fault for its poor relationship with him. He pointed to a 2019, incident that occurred long afterwards he broke off advice with The Voice over reports on the schoolhouse's exam scores.

Later on the land education department named a Fairfield instructor S.C. Teacher of the Year, a tweet from a Voice freelancer noted that Dark-green sits on the same panel that selects the award.

Greenish took the remark every bit a slight that suggested the Fairfield teacher did not earn her recognition. "Just despicable!!" he tweeted at the time.

The Phonation's publisher responded, "FCSD is rightfully proud of her accomplishment, every bit is all of Fairfield County."

But Green told his employees that he does non trust The Voice — and that they should not either.

A steep fee

In 2019, The Voice requested access to records documenting two years of Green's discretionary spending — an issue that had continued to divide members of the lath.

After waiting 10 business organisation days to respond, the maximum immune under country law, Green insisted the information would cost $338. The Vocalisation couldn't beget to pay.

State police allows governments to waive fees and release public information for gratis, and so The Voice asked Green to reconsider.

He waited another two weeks, then refused. He also rejected the paper's requests to audit the records in person, something reporters often do to avoid the costs of copying documents.

Asked almost the thing by The Post and Courier, Greenish said he'south merely doing what the law allows him to do.

The Voice has a team of freelancers and i full-time editor and the publisher, who declines a salary. The publisher also supplements a roughly $150,000 annual budget past occasionally paying for hire and other expenses out of her ain pocket.

Ultimately, The Voice dropped its request.

The paper agreed to partner with The Postal service and Courier on this article, in part, in an attempt to obtain Green's spending records — originally sought nearly two years ago.

When The Postal service and Courier sent its own request, for travel expenses from 2017-20, Greenish agreed to plow them over without a accuse.

No word

The records show a steady drip of travel expenses for Green and his assistant. There's too a bulk of purchases related to a Bow Necktie Social club trip (for the district'south teenage boys), led by Green, to Louisville, Ky., in 2019. While board approval is required for trips costing over $600, overnight trips and out-of-state trips, Light-green did non enquire the board to approve the Louisville trip in advance, equally is required for all three travel criteria. When later asked almost the trip's expenses at a board meeting, Light-green said he couldn't recall details.

The bodily cost to taxpayers? More than $ten,100. That included lodging at the downtown Marriott; a $3,850 tour charabanc for students; and more than $700 in charges at the Louisville Slugger Museum, the Muhammad Ali Center and the world-famous Churchill Downs equus caballus racing track, domicile of the Kentucky Derby. Dark-green told The Post and Courier those expenses only covered costs of admission.

Hartman, ane of the board members, unsuccessfully sought details about that trip. Green also rebuffed her attempts to learn how much he earns each year.

"We never got whatsoever information we wanted," Hartman said.

At a 2018 board meeting, Hartman pressed for details of Green'south compensation. By that point, his bacon had steadily increased over vi years. His board-approved contract also entitled him to tens of thousands of dollars in annual contributions to his retirement account.

Simply when Hartman asked him how much money he made, Dark-green said he didn't know.

Now, Green's bacon has ballooned to more than $192,000. No superintendent of such a pocket-sized commune in South Carolina makes more, according to the almost recent data from the state. Including his retirement benefits, his overall taxpayer-funded compensation is above $225,000.

Green told The Post and Courier he has agreed to freeze his benefits package at its current level.

"That'southward what my spirit led me to exercise," he said.

Pricey trips

Other records obtained by The Post and Courier testify even more expenses — these charged by Fairfield's 7 board members for their travel.

In just over iii years, board members charged taxpayers more $123,000 in expenses for travel to conferences, including $52,900 in out-of-state travel.

It too included most 70 trips to waterfront resorts in Charleston, Myrtle Embankment and Hilton Head. During school years, one or more schoolhouse board members attended a conference simply about every month, the records show.

The board'southward travel between 2017-xix averaged $41,200 a year. By comparison, in the last full fiscal yr before the pandemic, the board of Greenville schools spent less than $37,000 on travel. That board oversees the largest district in Due south Carolina. And information technology has 12 members, five more Fairfield.

Fairfield lath members disclosed their trips in reports provided during regular meetings. Merely they had trivial to add to inquiries from The Mail and Courier. Near did non respond to phone messages and emailed questions about their travel.

The board's chair, Henry Miller, has charged the most in recent years — more than $31,500, records show. He did not render voicemails, but defended the travel in a written response.

"Investing in preparation and professional development is a vital component to becoming a more than effective school board fellow member," he said.

Another sitting board member, Sylvia Harrison, spent more than than $27,000, records prove. She also briefly dedicated her travel. But after learning the paper was partnering with The Voice, Harrison said she wasn't interested in a reporter'due south questions.

"This is what y'all all do," Harrison said. "It didn't work for (The Voice) and information technology'southward non going to work for you."

Few comments

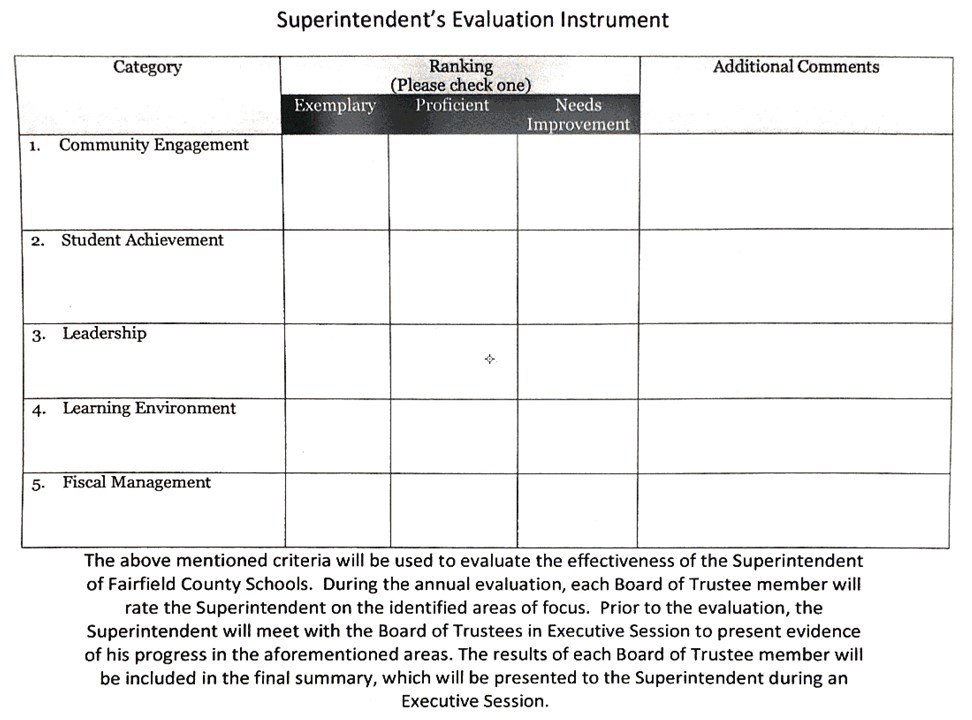

Green is supposed to receive more than scrutiny during his annual evaluations from the board. But yr after year he glides through the process, often without being pressed publicly on any aspect of his functioning.

The lath conducts its year-stop discussions with Green behind closed doors. Then, board members submit one-folio rubrics with benchmarks as vague as "community engagement." The evaluations exercise non point to any measurable goals.

Board members do not take to sign their names, nor are they required to offer specific comments on how well the superintendent stacked upward. Some leave no comments at all.

By comparison, Fairfield'south neighbor in Richland County School District Two, board members there evaluate their superintendent with vi-page forms using far more detailed metrics.

State Representative Annie McDaniel, who sat on the school board from 2000-18, said Fairfield used to use a similar process. But some time during Greenish's tenure the board pushed for a change.

"We went to a one-pager," McDaniel said. "I wasn't a fan of it, even though I thought that Dr. Greenish was doing some expert things in the district," she added.

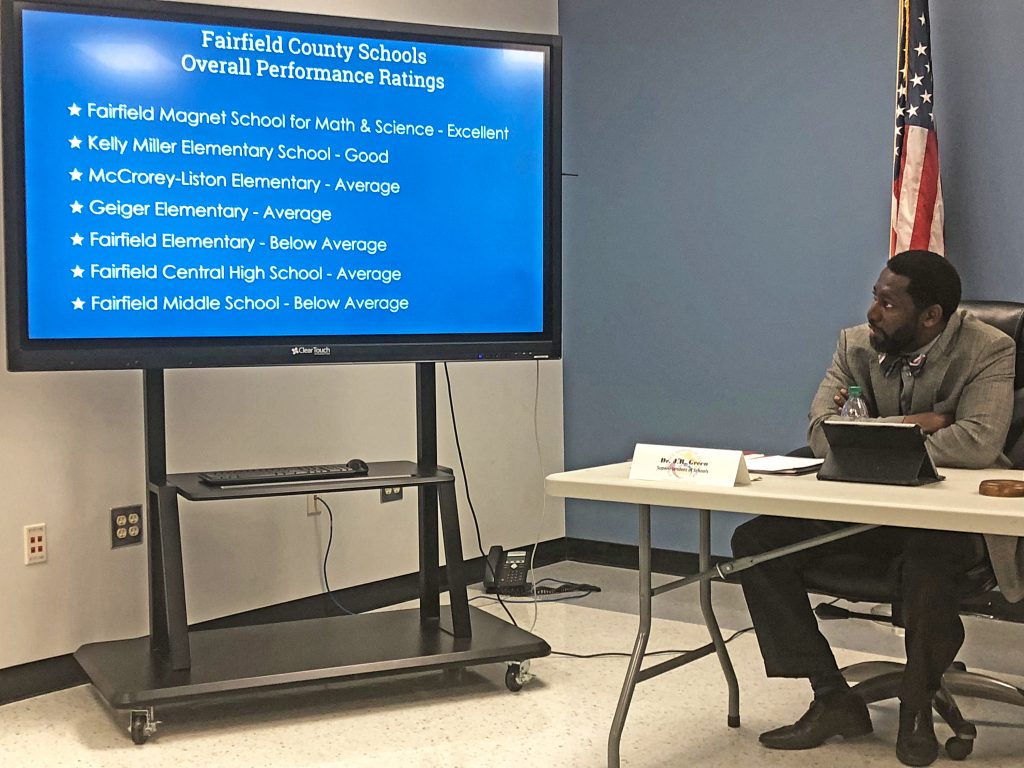

Meanwhile, though the country has adjusted its metrics, Fairfield schools take near the same overall 'average' rating as when Green took the helm eight years ago.

In an interview, Light-green defended the commune'southward piece of work with students and stressed that top officials continue to brand changes. Nearly recently, after poor ratings in 2019, Green replaced the middle school principal.

"I'm never satisfied," he said. "We recognize that we even so have progress to exist made."

'Negative' coverage

Ultimately, it was the low ratings for Fairfield Heart School, and other middling district metrics, that were the subject field of The Voice commodity in 2018 that fix Green off.

He blasted the publication in his email to principals and other staff. 2 months later, he took the affair a stride further: He started Fairfield school district's own newspaper, The Fairfield Post.

The newspaper features bylines from students. But with articles on community events and local elections, its coverage stretches well beyond the walls of Fairfield schools.

Every bit Dark-green puts it, "Anyone tin submit a story."

Local politicians regularly oblige. An early issue included a half-page editorial on education policy, written by state Sen. Mike Fanning. Another edition contained an unsigned feature on Green, after he received a special recognition from USC.

Throughout 2020, inside pages were filled with campaign advertisements and other content submitted past McDaniel, Winnsboro Mayor John McMeekin and Fairfield school lath candidates.

Sen. Greg Hembree, the country senate educational activity chair, told The Postal service and Courier that Dark-green has waded into murky ethical territory, where the public underwrites a news publication with petty ability to keep information technology from becoming a "propaganda arm" of the district.

Green told The Mail and Courier he has no editorial control over the newspaper. He but reads and encourages the publication. Politicians pay for their advertisement infinite, Light-green said.

Not everyone is convinced The Fairfield Post is a good idea.

Teague, with the League of Women Voters, said she's not sure the organization is legal.

"The paper is a public resource, and it is being used for entrada purposes," she said.

Green insists he did not start The Post to compete with The Voice.

"I'grand not stopping them from writing anything," he said, only neither is any information allowed to be released from the district to The Vocalization.

Harrison, the lath member, besides defended The Post while railing confronting coverage in The Voice.

She told The Post and Courier, "If information technology'southward not positive, I don't read it."

After hanging upwards on a reporter, Harrison took to Facebook that evening to warning her followers most what she described as the latest example of biased news reporting. She insisted she had no intention of reading this commodity.

Besides, she added, "Nosotros have our own newspaper."

Joseph Cranney is an investigative reporter in Columbia, with a focus on government corruption and injustices in the criminal legal system. He tin can exist reached securely past Proton mail at [e-mail protected] or on Signal at 215-285-9083.

Avery One thousand. Wilks is an investigative reporter based in Columbia. The USC Honors Higher graduate was named the 2018 Due south.C. Journalist of the Twelvemonth for his reporting on South Carolina'southward nuclear fiasco and abuses within the state's electric cooperatives.

Barbara Ball is the publisher of The Voice of Fairfield Canton and The Voice of Blythewood. Ball received the South Carolina Press Association'south Jay Bender Award for Assertive Journalism in 2018 and 2019. She can be reached at [email protected]

Source: https://www.blythewoodonline.com/2021/05/sc-superintendent-battled-the-local-newspaper-then-he-used-public-money-to-start-his-own/

0 Response to "Fairfield County Sc Percentage That Cannot Read"

Post a Comment